The Presence of Absence

Rebecca Choi

Rebecca Choi

The Greeks tell us that Sisyphus received a curse as punishment from the gods that left him forced to repeatedly push a rock up a mountain, only to see it roll down once he reached the top. The frustration found in unending labor is one of the prevailing lessons to be extracted from the myth of Sisyphus, and is perhaps best interpreted by Roland Barthes, who consumed by the death of his mother, described his search to reclaim her essence as nothing short of a crippling cycle of grief. When confronted with her image in photographs and dreams, he explains to be “thereby compelled to perform a painful labor…struggling among images partially true, and therefore totally false. For I often dream about her (I dream only about her), but it is never quite my mother. I dream about her, I do not dream her. And confronted with the photograph, as in the dream, it is the same effort, the same Sisyphean labor: to reascend, straining toward the essence, to climb back down without having seen it, and to begin all over again.”[1] In art history, Barthes’s contemplation of an irrecoverable presence gave us the theoretical framework to discuss the art of the index, and in fact paved the way for site-specific art practices interested in the particularities of trace and location. [2] Rarely has the act of Barthes’s incessant search, the performance itself, been discussed as a symptomatic action that—through repetition—bound him to the memory of his mother.

It is in his pursuit to translate this tension found in familiarity that Los Angeles based artist Sean Shim-Boyle explores perceptions of absence in his most recent sculptural and installation work at SIGNAL. Layering myth, memory and trace, the artist uses structural interventions, wall drawings and a set of automatic sliding doors that challenge traditional sculptural vocabulary, blurring the conceptual boundaries between art and architecture in a manner exemplary of the shared territory between architecture and sculpture in the expanded field. In order to arrive at his current work, Shim-Boyle compressed two sliding doors commonly found in commercial buildings to a height lower than is allowable by code and stripped them of their operative function to open and close. Locked in an endless stand off, the arresting movement produces what would appropriately be described as a highly phenomenological experience when standing near, within, and around the tenuous passageway; however, even a brief encounter with the doors reveals that the same, repetitive movement are in fact symptomatic of a more elaborate condition. The doors sense something that is not there, and Shim-Boyle deliberately sets out to make you see this figurative exchange as his first explicit marker to capture an elusive memory. By teasing out what would become the structural residue of a building such as electrical conduits and support brackets, the gallery space begins to harbor a general malaise and perhaps even an ambivalent uncertainty characteristic of contemporary Americana.

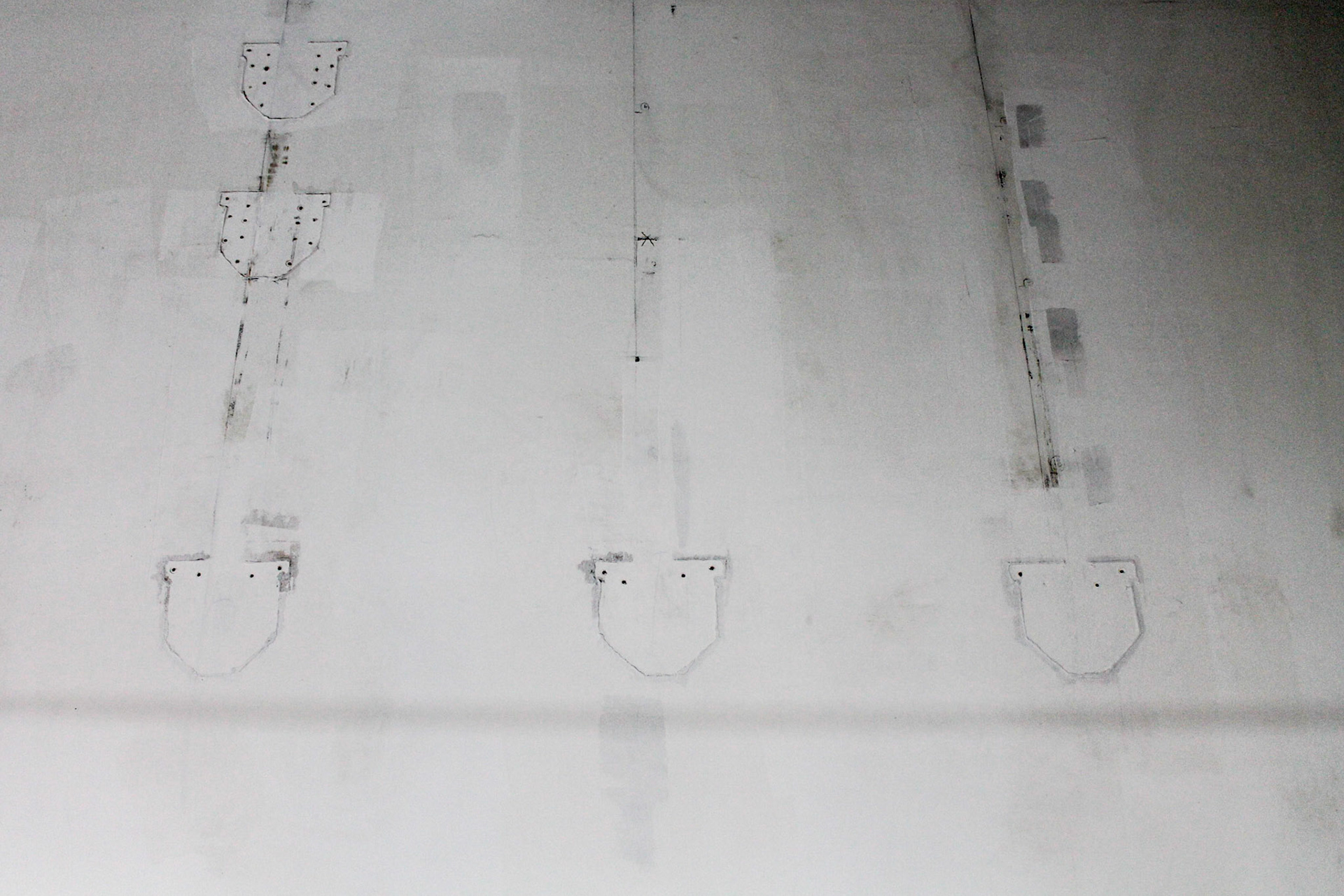

The most enigmatic of Shim-Boyle’s work is his foregrounding of a past recuperated in the form of wall drawings. The drawings, produced by rafters installed and then removed, are the result of a newly absent construction, and in fact reverse the operational premises of drawings as we understand it. The vertical surface of the wall bares the mark of labor and serves as a continuously coded flat plane where the artist has produced scuff-marks, punctures and other traces of ceiling joists being wedged and pressured into place. The capacity of Shim-Boyle’s work to capture the metaphysics of architecture is precisely what Rosalind Krauss read in Gordon Matta-Clark’s ‘floor cuts’ and Michelle Stuart’s ‘wall rubbings,’ each who used the syntax of the building to force site and context into the conceptual field of sculpture.[3] Their work exploited architecture’s fixed organization and arrangement of its floors, walls and ceilings, drawing attention to the material presence of the building and the memories that lurk beneath. Matta-Clark accomplished this through indexical cutouts and Stuart through imprinting traces, and while Shim-Boyle’s work seemingly use both procedures of implanting and removing, he in fact uses this heritage as a means to appropriate site as a mutable condition rather than point to an authentic original or a single past. In his provocative rehearsal of Sisyphus, Shim-Boyle mobilizes allegorical narrative in order to recast myth. Even in the case of the doors, however long we perform Minimalism’s request to understand our bodies in relation to the sculptural object, to find what’s obstructing closure, twin sensors reveal a closed loop, a collapsed system requiring no presence at all—only interminable absence.

[1] Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. Hill and Wang, 1982: 66.

[2] On site-specific art practices see Kwon, Miwon. One Place after Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2014.

[3] Rosalind Krauss, "Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America: Part 2" October 4 (Autumn 1977): 65.